The Kollmar & Jordan House in Pforzheim – Industrial History in Architectural Elegance

The Kollmar & Jordan House in Pforzheim – Industrial History in Architectural Elegance

Industrial History in Architectural Elegance

The Bleichstraße, branching off from Pforzheim’s Sedanplatz, was developed with side streets during the Gründerzeit era, bringing forth both grand residential buildings and factories. From 1911 onwards, the city tram ran along Bleichstraße, which had been named after the historic bleaching meadows once located there. In earlier times, the riverside meadows south of the city—between the Nagold, Metzelgraben, and Bleichstraße—were used for bleaching laundry. The textile industry’s growing need for bleaching and dyeing agents led to the establishment of a “Salmiak works” on the outer Bleichstraße in 1804, which was acquired in 1823 by Johann A. Benckiser and expanded into a chemical factory.

Today, anyone walking along Pforzheim’s Bleichstraße is inevitably drawn to a striking building complex, remarkable for its colorful brick façade, glazed surfaces, and ornate details: the Kollmar & Jordan House. Once a bustling center of jewelry production, it has since been transformed into a place of culture, education, and memory—a building that fascinatingly bridges past and present.

From Jewelry Factory to Cultural Monument

The story of the house begins in the late 19th century. Entrepreneurs Emil Kollmar and Wilhelm Jourdan founded their jewelry and watch chain factory, Kollmar & Jourdan AG, in 1885, which quickly grew into one of Germany’s most significant jewelry manufacturers. To meet the demands of its expanding production, a factory complex was built between 1901 and 1910 along Bleich-, Hans-Meid-, Kallhardt-, and Schießhausstraße, designed as a steel-frame structure. Architect Hermann Walder created a complex that combined industrial functionality with artistic ambition—a hallmark of the era in which Pforzheim, the “Golden City,” earned international renown. At times, more than 1,000 employees worked here.

The corner building at Bleichstraße 77 was added in 1922, also designed by Hermann Walder’s Karlsruhe office, serving as an office building for the jewelry and watch chain factory. A bridge connected it directly to the factory complex. The façade is adorned with five busts decorated with jewelry, each symbolizing one of the world’s continents—an allegory of the company’s global business relations, which extended as far as the Russian Empire and South America.

Art Nouveau Meets Industrial Architecture

Architecturally, the building is immediately eye-catching: green-glazed bricks, white structural elements, and reddish-brown accents. A cladding of colorful glazed ceramics in green, red, and cream tones gives the building its extraordinary appearance. Particularly impressive are the ceramic medallions with relief depictions of the five continents—a symbol of the worldwide trade in jewelry and precious metals in which Pforzheim played a central role. Over one entrance, a Gothic-inspired supraporte showcases the era’s fondness for creative detail.

For photographers, the building offers an inexhaustible play of lines, ornaments, and colors. Its façades are not only relics of industrial history but also outstanding subjects for architectural photography.

Transformation After the War

On February 23, 1945, large parts of Pforzheim were destroyed in an air raid. The Kollmar & Jourdan House survived partially, but its northeastern wing along Hans-Meid- and Kallhardtstraße was almost completely destroyed. Crowning corner towers, gables, and roofs also fell victim to the bombs. Reconstruction began under Max Kollmar after the war and was completed by 1949, though in a much more functional form: flat roofs and staggered stories replaced the original steep roofs, corner towers, and gables.

The golden years, however, were over. In 1977, the Kollmar & Jourdan jewelry and watch chain factory went bankrupt and was liquidated. Fortunately, the value of the building was recognized: in 1978 it was placed under historic preservation, and in the following decades it was adapted for new uses.

Today: Culture, Learning, and Exchange

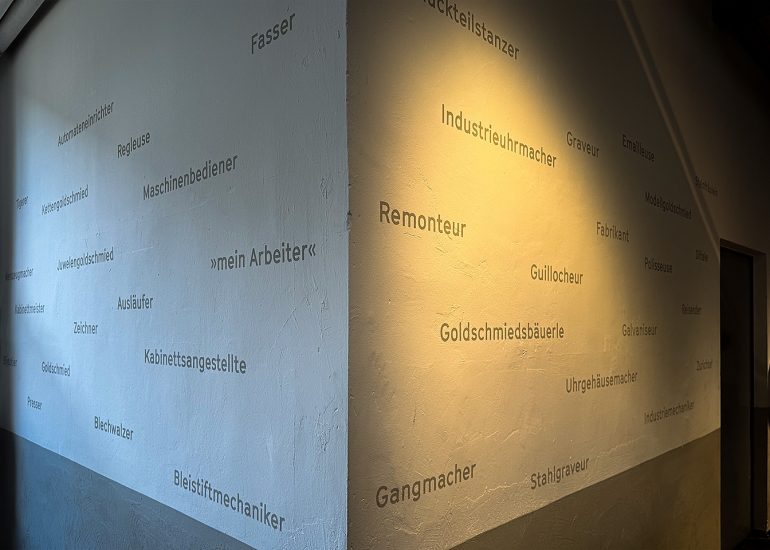

Today, the house is as lively as ever—though in a very different way. Beginning in 2012, the building was renovated and converted into a commercial property. The northern wing now houses the Technical Museum of Pforzheim’s Jewelry and Watch Industry, redesigned in 2017, which vividly documents the city’s industrial past. Historic machines still stand in the former production halls, bearing witness to the labor of generations. The upper floors of the former factory are now home to the Pforzheim Gallery and the Carlo Schmid School, along with offices and studios.

The Technische Museum der Pforzheimer Schmuck- und Uhrenindustrie is particularly impressive, showcasing a collection of historical machinery. Across 18 stations, visitors can experience production steps and techniques typical of Pforzheim’s jewelry industry. Rather than representing a single historic factory, the machines come from various companies and periods. Some factories specialized in specific processes, while others offered a deep vertical integration, covering numerous stages of production.

Comments are closed.